Yesterday I was reading a recent article in an online journal I follow closely. The article, entitled "Benjamin Church, The First American Ranger" recounts the exploits of none other than Benjamin Church, that soldier for Plymouth Colony who took part in the Great Swamp Massacre and who is credited with incorporating Native American stealth tactics into fighting in the various wars of that age, down through to today.

One of those forgotten men is a Rhode Islander who played a pivotal role in saving the English New Englanders from losing the war to the Indian leader, Metacom, or as the English knew him, King Philip, and his allied warriors. The Rhode Islander did so by learning and implementing the superior war tactics of the Indians during the summer of 1676. Along with his contribution to the English victory he also set in motion a new style of war that would be used for hundreds of years in North America. These tactics helped America claim its independence from Great Britain and an evolved version of these tactics are still used to this day by one of America’s most elite military units, the United States Army Rangers. This largely forgotten man is Benjamin Church and he was the “The First American Ranger.”

Benjamin Church's other great claim to fame was identifying the body of Metacom (King Phillip) after he was assassinated by Wampanoag "praying Indian" John Alderman. Church, by his own account, ordered Metacom's body to be drawn and quartered. Phillip's head was taken to Plymouth and left on a spike that overlooked the town for decades after.

Drawing, quartering, and spiking heads is all a bit medieval, but that was New England society in the seventeenth century. A bit medieval.

But the article never mentions that, or looks critically at the primary source that much of this narrative draws upon. I am not a fan of writing that celebrates as heroes violent men responsible for slaughtering Indigenous peoples. Or writing that takes a biased primary source at face value without providing necessary context or any critical examination. It is an interpretation more typical of histories written in the 1920s than in the 2020s.

And I take offense to another inaccuracy made repeatedly in this narrative: that Church was a Rhode Islander.

As a Rhode Islander, I will refute that claim this morning then head off to celebrate my birthday at the Newport Jazz Festival.

According to the genealogical website "Church [Family] History in America" Benjamin Church's father, Richard, arrived at Plymouth colony in 1630 with the same fleet that carried John Winthrop. Richard Church was a carpenter and he built the settlement's first Puritan meeting house of worship. Benjamin too was a carpenter, when he wasn't hunting down Indians, but more importantly he was a Puritan. Seventeenth-century Puritans despised Rhode Island and the heretics who dwelt there. In 1643 Plymouth, Massachusetts and the settlements that eventually became Connecticut formed the New England Confederation, to unite the militaries of the Puritan and Separatist colonies -- and deliberately left Rhode Island out of the alliance while making numerous claims against her territory. Massachusetts even invaded Rhode Island that same year to arrest Warwick's founder Samuel Gorton and drag him back to Boston. Nor was it the last time Massachusetts would.

I suspect Benjamin Church, an early second-generation Puritan, would be loathe to be referred to today as a Rhode Islander -- a rabble rife with Baptists, Gortonites, Antinomians, and Quakers.

Truth is, Benjamin Church never lived in Rhode Island.

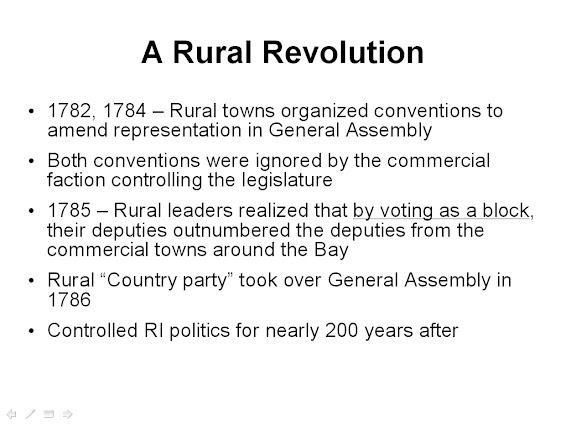

Fact check. Wikipedia claims that Church died on "January 17, 1718 (aged 78–79) [in] Little Compton, Rhode Island." However, Little Compton was originally part of the homelands of the Sakonnet people before the arrival of the Pilgrims in 1620, and remained so into the 1670s. Church built a house there in 1674 just a year prior to the outbreak of King Phillip's War. In 1682, after the English victory over the Indians of southern New England, Sakonnet was renamed Little Compton and officially incorporated into the Plymouth colony (see map below).

|

| Little Compton and Plymouth Colony, c. 1690. The area in the 2022 Google Map (below) is in the rectangle (above) Image credit: Tenterden and District Museum |

Then in 1685 Plymouth, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Haven, New York and East and West Jersey were reorganized into the Dominion of New England by King James II, until the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. In the aftermath, Plymouth, which had operated for over 70 years without a charter from England, was officially made part of Massachusetts Bay. Benjamin Church would have learned of this in the spring of 1692, when newly minted royal governor Sir William Phips arrived in Boston after William and Mary refused to grant him for a charter for Plymouth.

So Church's house started off in Sakonnet Indian territory, which after King Philip's War became Little Compton, a town in Plymouth, then Plymouth became Massachusetts. Then Church died and was buried in the Old Commons Burial Ground -- known today as Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Little Compton #12.

Little Compton remained a Massachusetts town until a boundary dispute with RI was resolved in Rhode Island's favor in 1747 (see the Mass/RI boundary above). However, Benjamin Church died 29 years earlier, when everywhere on this Google map was Massachusetts, not Rhode Island. It maybe a bit much to expect Wikipedia editors to notice this discrepancy, though someone should go in and fix that. If I cared enough about Benjamin Church having an accurate biography on Wikipedia I would probably do it myself.

So what about the argument that Benjamin Church was a Rhode Islander? Here is another section of the article that makes this claim:

Church was born in Plymouth Colony (now part of Massachusetts) in 1639 and learned to hunt and trap at a very early age. After marrying in 1667, Church eventually became one of the first settlers of “Sogkonate” (anglicized to Sakonnet) land that is now part of Little Compton, Rhode Island. Soon after his arrival in Rhode Island in 1674, he encountered the Sakonnet tribe...

This passage argues that Church arrived in "Sogkonate" in 1674, and that this was "in Rhode Island." It was not. It wasn't even part of Plymouth yet. In fact it wasn't even Little Compton yet, and it would not be part of Rhode Island until Benjamin Church had been dead and buried in the Massachusetts ground for nearly three decades.

Or more accurately, entombed just above the ground. if one were to visit the Old Commons Burial Ground (see Google Map above), Benjamin Church's place in the social structure of early Little Compton becomes clear. He and his entire family, including small children, are laid to rest in expensive altar tombs -- unlike the cemetery's other residents who are buried in the ground behind more modest headstones.

|

| Top, Benjamin Church's altar tomb (center), Old Commons Burial Ground (see map below). All these altar tombs in both photos are member's of Church's family. image credit: Caitlin GD Hopkins |

Now let us look at the problems that arise from taking a biased primary source at face value without providing necessary context. For that, let's turn to the research of Jillian Lepore (Harvard University's David Woods Kemper '41 Professor of American History), then the work of Guy Chet (Professor Of History at the University of North Texas).

Jillian Lepore explored the conflict in her 1998 Bancroft prize-winning book, The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity. For those who have not yet read Lepore's book, there are several well-produced videos online of her speaking about it, including this one she gave to the Gilder Lehrman Institute in December 2010. To summarize her lecture (and book), Lepore

…traces the meanings attached to [King Phillip's War]. Lepore examines early colonial accounts that depict King Philip's men as savages and interpret the war as a punishment from God, discusses how the narrative of the war is retold a century later to rouse anti-British sentiment during the Revolution and finally describes how the story of King Philip is transformed yet again in the early nineteenth century to portray him as a proud ancestor and American patriot. Through these examples, Lepore argues that "wars are just as much a contest for meaning as they are for territory, and wars are indeed just as much a contest for memory as they are for political allegiances."

|

| Jillian Lepore during a presentation on The Name of War, at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, December 1, 2010. |

The Name of War is a deeply researched and highly regarded interpretation of King Phillip's War... which the article in question never cites or references.

Lepore also provides a historically-grounded critique of Church's "The entertaining history of King Philip’s War" -- which she reads as not as a biography not by Church but a hagiography written by his son Thomas -- in her 2006 piece for The New Yorker, "Plymouth Rocked:"

"This as-told-to, after-the-fact memoir is the single most unreliable account of one of the most well-documented wars of the Colonial period. More than four hundred letters written by eyewitnesses in 1675 and 1676 survive in New England archives, along with more than twenty printed accounts, written as the war was happening, or very shortly thereafter. But even though “Entertaining Passages” was compiled forty years after King Philip’s War had ended and may well have been entirely written by Church’s son (who, at the very least, edited his father’s “notes” considerably)...[some historians have used] it without reservation or caution.

Similarly, Guy Chet's 2007 article in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts "The Literary and Military Career of Benjamin Church: Change and Continuity in Early American Warfare," questions two arguments this article makes: first, that Church is the progenitor of the US Army Ranger corps, and second, that he was instrumental to the English victory over the Wampanoag and their allies.

For a war that began in June 1675 and killed at least 10% of the region's inhabitants, Benjamin Church

"had an undistinguished career until the summer of 1676, when he...started to accumulate tactical victories over Indian forces. At that point the remaining mutinous tribes were already starving, weakened, politically isolated, and on the run from English and Indian forces (Chet 107).

Despite Church's heroic narrative that places him at numerous critical turning points of the conflict forty years after the fact, contemporary accounts written during the war hardly mention him. The most extensive account of his activities during the war were written by Boston minister Increase Mather, whose Brief History of the Warr With the Indians in New England (published in 1676) only mentions Church "in a July 1676 entry -- the closing stages of the war -- in which Mather states that Church recruited Indians to hunt other Indians" and "nothing...about Church being the conqueror of Philip." The other occasion Benjamin Church comes up in Mather's account was in a discussion of 1677 after the war was over, and in the book's Postscript. Other accounts written in 1675-1676 do not mention Church at all. (ibid 109).

As to how Church gained his reputation as an influential tactician and the father of the American small-unit tactical warfare, Chet finds it "striking about this wide-ranging credit is that Church seems to have won it posthumously" and that "Church's exploits, his story and legacy were products of the Jacksonian era more than the colonial period (ibid 108).

His memoirs, Entertaining Passages relating to Philip’s War, written in part or in full by his son Thomas, offer a narrative that, understandably, highlights Church's successes and places him at the center of the story of the war. However, Entertaining Passages was published forty years after King Philip's War (1716), so nobody could have read and learned from Church for at least four decades, unless it was by word of mouth. The second edition of Church's memoirs was published in 1772, almost a hundred years after the war. A third edition appeared in 1825...a fourth edition in 1827; a fifth in 1829; a sixth in 1834; a seventh in 1842 an eighth (in two volumes) in 1865 and 1867. A ninth edition appeared in 1975...and a digital version...in 1999 (ibid).

Chet's interest in Benjamin Church as well as another frontier fighter, Robert Rogers, as the genii of modern American warfare, are primary to the investigation of his 2003 book, Conquering the American Wilderness: The Triumph of European Warfare in the Colonial Northeast, the title of which is a bit of a spoiler here. A number of military histories regale both men as instrumental in the use of stealth, surprise, and deception that developed the uniquely American small-unit tactics that won the Revolutionary War for the United States. Chet sought to locate "the instructional mechanism by which the knowledge acquired by Church [and Rogers] was disseminated among colonial officers from one generation to the next." But he couldn't find it, because it did not exist.

What Chet discovered instead was that the stories about Church and Rogers being the fathers of the Ranger corps were ahistorical narratives centered in American exceptionalism and Turnerian glorification of the frontier long after the colonial era, rather than how the colonists and (later) the Americans actually fought in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In reality, what Chet uncovered was that most colonists (and the their militias) were far more aligned with the Atlantic world and British battle tactics than with the individualism and stealth of a hunter or Indian fighter on the colonial frontier (ibid 106).

So no, whatever the US Army's Ranger Handbook and the article "Benjamin Church, The First American Ranger" say to the contrary, Benjamin Church was NOT the father of the "American" stealth military tactics, nor did he play "a pivotal role in saving the English New Englanders from losing" King Philip's War.

Nor was he a Rhode Islander.

The reality was that actual Rhode Islander's -- both English and Indigenous -- intended to stay out of this brutal conflict. Rhode Island was INVADED by the United Colonies of Connecticut, Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay and their Pequot and Mohegan allies in December 1675. Their intention was to massacre the Narragansetts in their winter fort in what is today South Kingstown, just like Massachusetts Bay colonists and their Indian allies had done to the Pequot fifty years earlier. And not only Narragansett warriors but their elders, women and children. Men like Benjamin Church who, coming upon Metacom's assassination, according to his own "entertaining" story, called Phillip "a doleful, great, naked, dirty beast" as he lay bleeding to death on the ground (and if those are not words Thomas Church put in his father's mouth forty years after the fact).

Nonetheless, I would argue that passage says more about how Church really felt about Indigenous people than the kumbaya story that "Benjamin Church, The First American Ranger" relates about Church breaking bread with Wampanoag sachem Anawan after capturing him in the summer of 1676. Another story from the Entertaining Passages Relating to Philip’s War that, like nearly that entire source, is not corroborated anywhere else.

While Church is remembered rightfully as one of the early founders of Little Compton, he was NEVER a Rhode Islander. Just because his grave happens to be in Rhode Island now, that isn't our fault.

_________________________________________________

Bornt, Daniel J. "The Church Family in America 1630-1935" in The Church Family of Petersburgh, NY featuring descendants of Frank and Myrtle Church, 2002. https://churchtree.tripod.com/churchhist.html

Chet, Guy, The Literary and Military Career of Benjamin Church: Change and Continuity in Early American Warfare. Historical Journal of Massachusetts, January 2007.

Hopkins, Caitlin, "Benjamin Church" Vast Public Indifference: History, grad school, and gravestones! May 30, 2009. http://www.vastpublicindifference.com/2009/05/benjamin-church.html

Lepore, Jillian, "Plymouth Rocked: Of Pilgrims, Puritans, and professors." The New Yorker, April 24, 2006. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/04/24/plymouth-rocked

- The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1999.

- "The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity" by Jill Lepore, History Resources, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Uploaded December 1, 2010. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/videos/name-war-king-philip%E2%80%99s-war-and-origins-american-identity

Padula, Kevin, "Benjamin Church, The First American Ranger." The Online Review of Rhode Island History, July 30, 2022. http://smallstatebighistory.com/benjamin-church-the-first-american-ranger/

.jpg)

.png)