These well-received overviews of US history since WWII (Grand Expectations won a Bancroft Award in 1997) have made Patterson eminently qualified to speak on what he has identified as the "hinge year", the turning point where post-World War America shifted from the conformist “All-American” culture of the ‘Long 1950s’ (which began perhaps in 1945 with the end of WWII) to the explosive counterculture of the 1960s. While many commentators on the period tend to point to the assassination of JFK in November 1963 as the “end of innocence,” or the arrival of the Beatles in America in early 1964 as the crucial cultural turning point, Patterson argues that the real “sixties” doesn’t begin until 1965. The “decade approach” to American history works for some periods – the 1920s, the 1930s, and possibly the 1980s and 1990s tend to fall into ten year chunks, but the 1950s and 1960s are problematic in this regard. Patterson’s take is that 1965 is really the beginning of the 1960s that looms large in the public imagination – the protests, the violence, the Vietnam war, the counterculture, the music and Woodstock.

Patterson began his talk at the Fabre Line Club with the confession that he is not the first to describe 1965 as the “hinge” year of the 1960s. In 1995, the renowned conservative George Will had pointed out 1965 as a pivotal turning point in American history, not to mention the much-less regarded conservative, Newt Gingrich, has done so as well.

Patterson’s argument is that the triumph of liberalism was at hand in 1964. With his landslide victory over Barry Goldwater (486 to 52 in the Electoral College), and the domination of the Democratic Party in both houses of Congress, Johnson’s hubris brought him to make this almost surreal speech at the lighting of the national Christmas tree in December 1964:

…These are the most hopeful times in all the years since Christ was born in Bethlehem.

Our world is still troubled. Man is still afflicted by many worries and many woes.

Yet today--as never before--man has in his possession the capacities to end war arid preserve peace, to eradicate poverty and share abundance, to overcome the diseases that have afflicted the human race and permit all mankind to enjoy their promise in life on this earth.

At this Christmas season of 1964, we can think of broader and brighter horizons than any who have lived before these times. For there is rising in the sky of the age a new star--the star of peace.

By his inventions, man has made war unthinkable, now and forevermore. Man must, therefore, apply the same initiative, the same inventiveness, the same determined effort to make peace on earth eternal and meaningful for all mankind.

Grand expectations indeed. From there, Johnson, consummate master of Washington politics and Capitol Hill, took full advantage of his election mandate. LBJ’s Great Society picked up where FDR’s New Deal left off: Medicare, Medicaid, immigration reform, the Voting Rights act of 1965, the War on Poverty, the Education Act of 1965 – a stunning feat of serial legislative engineering that remains unparalleled to this day.

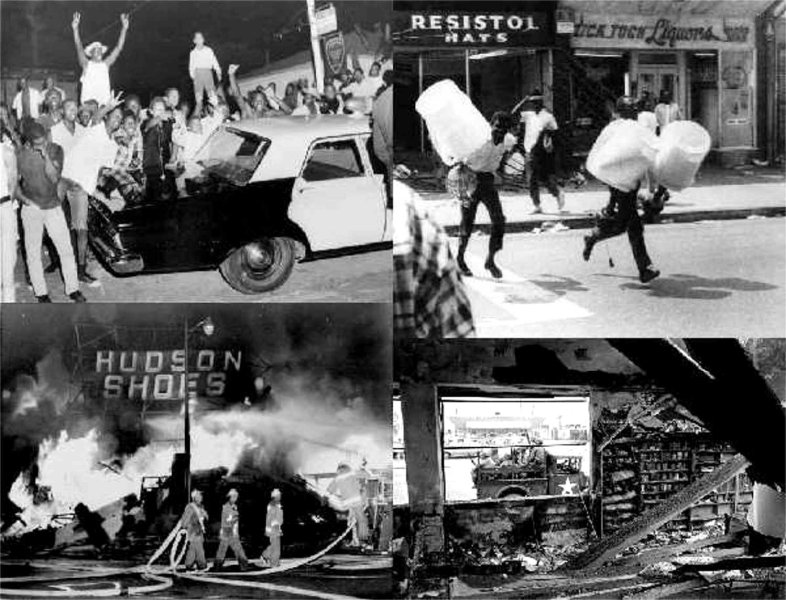

But at the Christmas tree lighting of 1965, Johnson did not follow up on his bombast from the year before as the liberal triumphant. What had humbled him? Patterson carefully expounded on the escalation of war in Vietnam, Selma, the rise of Black Power and the open fragmentation of the civil rights movement, the Watts riots which exploded only days after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, the first teach-ins, the rise of the SDS and resistance to the draft… all this violence and discontent turned the country almost on a dime.

The “grand expectations” of America were brought to heel in a flood of uncertainty that really began, Patterson convincingly argues, in 1965. The year began with the Beatles “I Feel Fine” as the number one song in America. But by late September, P.F. Sloan’s "Eve of Destruction" as sung by Barry McGuire was number one. Patterson then played a cassette tape (which is in itself an analog relic in this age of digital music) of McGuire’s hit song while the room quietly listened.

The eastern world it is explodin',

violence flarin', bullets loadin',

you're old enough to kill but not for votin',

you don't believe in war, what's that gun you're totin',

and even the Jordan river has bodies floatin',

but you tell me over and over and over again my friend,

ah, you don't believe we're on the eve of destruction.

Don't you understand, what I'm trying to say?

Can't you see the fears that I'm feeling today?

If the button is pushed, there's no running away,

There'll be no one to save with the world in a grave,

take a look around you, boy, it's bound to scare you, boy,

and you tell me over and over and over again my friend,

ah, you don't believe we're on the eve of destruction.

Yeah, my blood's so mad, feels like coagulatin',

I'm sittin' here, just contemplatin',

I can't twist the truth, it knows no regulation,

handful of Senators don't pass legislation,

and marches alone can't bring integration,

when human respect is disintegratin',

this whole crazy world is just too frustratin',

and you tell me over and over and over again my friend,

ah, you don't believe we're on the eve of destruction.

Think of all the hate there is in Red China

Then take a look around to Selma, Alabama!

Ah, you may leave here, for four days in space,

but when you return, it's the same old place,

the poundin' of the drums, the pride and disgrace,

you can bury your dead, but don't leave a trace,

hate your next-door-neighbor, but don't forget to say grace,

and you tell me over and over and over and over again my friend,

you don't believe we're on the eve of destruction.

no no you don't believe we're on the eve of destruction.

I have used this song myself in teaching the 1960s – musically the song is a brilliant piece of folk-mainstream crossover -- a pastiche of Dylanesque protest folk with its acoustic guitar, harmonica, nasally vocals and references to Vietnam, Selma, and nuclear annihilation. Ironically, by the time McGuire’s song had replaced the Beatle’s pot-addled “Help!” in September 1965 as the number one song in America, Bob Dylan was in the midst of rejecting his identity as the voice of the 60s folk generation, plugging in at Newport and returning to his rock’n’roll roots by going on tour with The Band…

The questions and answer session after Patterson’s talk was nearly as interesting as the talk itself. He pointed out as the Q&A began that it appeared everyone in the room had lived through the year. I looked around in agreement – I was probably the youngest in the room, so I can attest that he was correct. I have to admit though I was alive in 1965, I can’t say I remember anything about 1965. I know I turned one that year. I had not yet quite reached my six month birthday on December 18, 1964, the day that Johnson compared his administration to the birth of Christianity. It was very enlightening to listen to people whose memories of the year were considerably more detailed than mine. For the most part, audience members saw their experiences as a microcosm located on Patterson’s larger canvas. The most remarkable exchange in the Q&A came when one gentleman, who had known Barry Goldwater personally, took exception to Patterson’s characterization of the Arizona senator as a deeply flawed candidate. Patterson listened politely then definitively tossed Goldwater back into the dustbin of history, pointing out the folly of Goldwater’s screed against the TVA in Tennessee, how his offhand remarks about nuking Vietnam and the Kremlin terrified millions and played right into Johnson’s hands, and the political suicide of calling for the abolition of Social Security while campaigning in Florida.

After the Q&A, I walked up to Dr. Patterson and introduced myself. We spoke about P.F. Sloan’s song and how emblematic it is as a cultural touchstone for this shift in the 1960s. I also explained to him that the history department where I teach has decided to use his Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974, as the thematic source for teaching this period of American history, as well as a basis for students’ research papers. He was genuinely pleased to hear a high school program was using his book, and asked me to let him know how it turned out. But like 1965, we will have to live through 2013 before we can evaluate its success.

For those who were not able to catch James Patterson’s talk at the Fabre Line Club on The Eve of Destruction: How 1965 Transformed America, David Scharfenberg conducted a short interview with James Patterson in the Providence Phoenix in December 2012. Patterson also appeared on BookTV’s After Words, an hour-long program recorded in November 2012, where Professor Daryl Scott and Patterson explore in depth many of the themes only briefly touched upon herein. Both are recommended followups to this essay.

____________________________________________________________________ Sources

James T. Patterson, The Eve of Destruction: How 1965 Transformed America. New York: Basic Books, 2012.

-- Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Lyndon B. Johnson: "Remarks at the Lighting of the Nation's Christmas Tree.," December 18, 1964. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=26766.

No comments:

Post a Comment